Table of Contents

Introduction

The Goods and Services Tax regime has revolutionized India’s indirect tax landscape, bringing with it robust audit mechanisms designed to ensure compliance and prevent revenue leakage. Among these mechanisms, GST audit under Section 66 stands as a critical tool in the hands of tax authorities, empowering them to conduct special audits when circumstances warrant deeper scrutiny of taxpayer records.

Section 66 of the CGST Act, 2017, represents a significant departure from traditional audit practices, offering authorities enhanced powers to examine business records and verify compliance. This provision has gained particular importance as tax authorities increasingly rely on data analytics and risk assessment to identify potential cases of non-compliance or tax evasion.

Understanding the nuances of GST audit under Section 66 becomes crucial for tax professionals, businesses, and compliance officers who navigate the complex landscape of GST regulations. The provision not only affects how audits are conducted but also shapes the strategic approach businesses must adopt to ensure seamless compliance with GST requirements.

Understanding GST Audit Under Section 66

Legal Framework and Statutory Provisions

Section 66 of the Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, titled “Special Audit,” provides the legal foundation for conducting specialized audits beyond the routine assessment procedures. The section reads:

“Where at any stage of scrutiny, inquiry, investigation or any other proceedings before him, any officer not below the rank of Assistant Commissioner is of the opinion that— (a) the value has not been correctly declared or the credit availed is not within the normal limits; or (b) the tax has not been paid on the value; or

(c) in general, the books of account and other documents are so maintained that it is difficult to determine the correct tax liability, he may, with the prior approval of the Commissioner, direct such registered person by a written order to get his books of account audited by a chartered accountant or cost accountant, as may be nominated by the Commissioner in this behalf and submit a report of such audit within such period as may be specified in the order.”

This provision establishes a framework where tax authorities can mandate special audits when they suspect irregularities or when conventional assessment methods prove inadequate to determine the correct tax liability.

Key Components of Section 66

The statutory language of Section 66 reveals several critical components that shape its application:

Triggering Conditions: The section identifies three specific circumstances that can trigger a special audit. These conditions provide authorities with flexibility while establishing clear parameters for invoking this provision.

Authority Level: Only officers not below the rank of Assistant Commissioner can initiate proceedings under Section 66, ensuring that such decisions involve appropriate seniority and expertise.

Commissioner’s Approval: The requirement for prior approval from the Commissioner adds an additional layer of oversight, preventing arbitrary use of these powers.

Professional Audit: The mandate for audit by chartered accountants or cost accountants ensures professional standards in conducting such examinations.

Circumstances Leading to Section 66 Audit

Tax authorities typically invoke Section 66 when they encounter situations that raise red flags about a taxpayer’s compliance. These circumstances often emerge during routine scrutiny or investigation processes, where preliminary findings suggest deeper issues that warrant specialized examination.

The first trigger relates to incorrect declaration of value or credit availment beyond normal limits. This encompasses situations where businesses may have understated their taxable supplies or claimed input tax credits that appear disproportionate to their business activities. Tax authorities often identify such cases through data matching exercises or industry benchmarking studies.

The second trigger addresses cases where tax has not been paid on the correct value of supplies. This can occur when businesses adopt aggressive tax positions or engage in practices that effectively reduce their tax liability below what authorities consider appropriate for their business profile.

The third trigger is perhaps the most comprehensive, covering situations where the maintenance of books of account makes it difficult to determine correct tax liability. This catch-all provision allows authorities to address cases where record-keeping practices, intentionally or otherwise, obscure the true nature of business transactions.

Detailed Analysis of Section 66 Provisions

Procedural Requirements

The procedural framework established under Section 66 emphasizes due process while providing authorities with necessary flexibility to conduct thorough examinations. The process begins with the formation of opinion by the designated officer, followed by securing necessary approvals and issuing formal directions to the taxpayer.

Formation of Opinion: The officer must form a specific opinion based on one or more of the prescribed circumstances. This opinion cannot be arbitrary but must be based on material available during scrutiny, inquiry, or investigation proceedings.

Prior Approval Mechanism: The requirement for Commissioner’s approval serves multiple purposes. It ensures consistency in the application of Section 66 across different cases, prevents misuse of powers by lower-level officers, and provides an opportunity for reviewing the merits of proposed audit directions.

Written Order: The direction for special audit must be communicated through a written order, which should specify the scope of audit, the nominated professional, and the timeline for completion. This requirement ensures transparency and provides taxpayers with clear understanding of expectations.

Nomination of Auditor

The power to nominate chartered accountants or cost accountants rests with the Commissioner, introducing an element of control over the audit process. This nomination system serves several purposes:

Independence: By allowing authorities to nominate auditors, the system aims to ensure independence from the taxpayer, reducing the risk of biased or superficial examinations.

Expertise: Commissioners can select professionals with specific expertise relevant to the nature of business or the suspected irregularities.

Standardization: The nomination process enables authorities to work with professionals who understand their requirements and can deliver reports in the desired format.

Timeline and Compliance

Section 66 empowers authorities to specify timelines for audit completion, recognizing that different cases may require varying timeframes based on their complexity. The specified period should be reasonable, considering the scope of audit and the availability of records.

Taxpayers must ensure compliance with the timeline specified in the audit direction. Failure to comply can lead to adverse consequences, including the drawing of unfavorable inferences about the taxpayer’s compliance intentions.

Comparison Between Section 65 and Section 66

Understanding the distinction between Section 65 and Section 66 proves crucial for tax professionals and businesses, as these provisions serve different purposes within the GST audit framework.

Section 65: Audit by Tax Authorities

Section 65 of the CGST Act empowers tax authorities to conduct audits directly, without involving external professionals. This provision reads:

“The Commissioner or any officer authorized by him may undertake audit of any registered person for such period, at such frequency and in such manner as may be prescribed, to verify the compliance with the provisions of this Act or the rules made thereunder.”

Aspect | Section 65 | Section 66 |

Nature of Audit | Direct audit by tax officials | Special audit by nominated CA/CMA |

Triggering Event | Routine compliance verification | Specific suspicion of irregularities |

Auditor | Tax department officers | Chartered Accountant/Cost Accountant |

Frequency | Can be periodic/routine | Triggered by specific circumstances |

Authority Level | Commissioner or authorized officer | Assistant Commissioner with Commissioner’s approval |

Scope | General compliance verification | Focused on specific suspected irregularities |

Professional Expertise | Tax administration knowledge | Professional accounting/costing expertise |

Powers and Limitations Comparison

Parameter | Section 65 Audit | GST Audit Under Section 66 |

Initiation Authority | Commissioner or authorized officer | Assistant Commissioner (with prior approval) |

Prior Approval Required | No | Yes, from Commissioner |

Professional Involvement | Tax department personnel only | Mandatory CA/CMA nomination |

Cost Bearing | Government bears audit cost | Typically taxpayer bears professional fees |

Timeline Flexibility | Administrative discretion | Must specify reasonable timeline |

Appeal Rights | Limited during audit process | Can challenge audit direction |

Documentation Standards | Administrative requirements | Professional audit standards |

Report Format | Internal departmental format | Professional audit report format |

Key Triggering Circumstances for GST Audit Under Section 66

Trigger Condition | Description | Practical Examples |

Incorrect Value Declaration | Value not correctly declared or credit not within normal limits | • Input credit claims exceeding industry norms • Undervaluation of supplies • Disproportionate credit patterns |

Tax Not Paid on Value | Tax liability not discharged on correct taxable value | • Suppression of taxable supplies • Incorrect tax rate application • Revenue leakage identification |

Difficult Tax Determination | Books of account maintained in manner making tax liability determination difficult | • Poor record maintenance • Complex transaction structures • Insufficient supporting documentation |

Fundamental Differences in Approach

The philosophical difference between these sections reflects the GST system’s multi-layered approach to compliance verification. Section 65 represents the traditional approach where tax authorities directly examine taxpayer records, while Section 66 introduces professional expertise into the audit process.

Purpose and Objective: Section 65 audits focus on general compliance verification, ensuring that taxpayers have correctly implemented GST provisions across their business operations. These audits can be routine and may not necessarily indicate suspicion of wrongdoing.

Section 66 audits, conversely, are triggered by specific concerns about the correctness of tax treatment or the adequacy of record maintenance. These audits target particular aspects of taxpayer behavior that have raised red flags during preliminary examinations.

Professional Standards: The involvement of chartered accountants or cost accountants in Section 66 audits brings specialized professional standards to the examination process. These professionals must conduct audits in accordance with their respective professional standards, potentially providing more detailed and technically sound reports.

Practical Implications of the Differences

From a taxpayer’s perspective, receiving a notice under Section 66 carries different implications compared to a Section 65 audit notice. The former suggests that authorities have identified specific concerns that warrant professional examination, while the latter may be part of routine compliance monitoring.

Preparation Requirements: Section 66 audits often require more extensive preparation, as taxpayers must be ready to explain specific transactions or practices that have attracted authorities’ attention. The professional auditor may demand detailed explanations and supporting documentation for particular aspects of business operations.

Cost Implications: While Section 65 audits involve administrative costs related to staff time and document preparation, Section 66 audits additionally involve fees payable to the nominated professional. Though the Act doesn’t explicitly address who bears this cost, practical considerations often place this burden on the taxpayer.

Judicial Interpretation and Case Law Analysis

The application of GST audit under Section 66 has witnessed several judicial interventions that have shaped its practical implementation. While the provision is relatively recent in the GST framework, courts have begun establishing important precedents that guide both taxpayers and tax authorities.

Industry Benchmarking and Audit Triggers

One significant area where judicial clarity has emerged relates to the use of industry benchmarking for triggering GST audit under Section 66. Tax authorities often rely on comparative analysis with industry peers to identify potential cases warranting special audit. The courts have generally supported this approach, but with important caveats.

The judicial view emphasizes that statistical variations alone cannot justify invoking Section 66 powers. Authorities must demonstrate specific reasons beyond mere mathematical differences from industry averages. This balanced approach recognizes the legitimacy of risk-based audit selection while preventing arbitrary use of special audit powers.

What’s particularly interesting is how courts have interpreted the phrase “not within normal limits” in Section 66(a). Rather than accepting rigid statistical thresholds, judicial pronouncements have favored a contextual approach that considers business-specific factors. This interpretation protects genuine businesses with unique operational models while maintaining the effectiveness of the audit provision.

Error Patterns and Record Maintenance Issues

Another crucial area of judicial interpretation involves the treatment of errors in taxpayer records. Courts have consistently held that the intent behind errors is not the primary consideration for GST audit under Section 66. Whether errors are genuine mistakes or deliberate attempts at non-compliance, the focus remains on their impact on tax liability determination.

This judicial stance reflects a practical understanding of tax administration challenges. When record-keeping practices, regardless of underlying intent, make it difficult to ascertain correct tax liability, Section 66 provides an appropriate remedy. The courts have emphasized that taxpayers cannot escape audit scrutiny merely by claiming that discrepancies result from innocent errors.

The implications for businesses are significant. Companies must ensure that their record-keeping systems are robust enough to withstand scrutiny, even when genuine mistakes occur. The judicial interpretation suggests that patterns of errors, even if individually explainable, can collectively justify special audit under Section 66.

Due Process and Procedural Safeguards

Judicial decisions have also reinforced the importance of due process in GST audit under Section 66 proceedings. Courts have emphasized that the formation of opinion by the designated officer must be based on material evidence, not mere suspicion or conjecture. This requirement serves as an important check against arbitrary exercise of audit powers.

The requirement for Commissioner’s prior approval has received judicial endorsement as a crucial procedural safeguard. Courts view this approval mechanism as ensuring consistency and preventing misuse of Section 66 powers by lower-level officers. However, they have also clarified that such approval should be meaningful, not merely a rubber stamp exercise.

Recent judicial trends suggest growing emphasis on proportionality in audit directions. Courts expect authorities to ensure that the scope and intensity of Section 66 audits are commensurate with the suspected irregularities. This balanced approach protects taxpayer interests while maintaining the effectiveness of the audit mechanism.

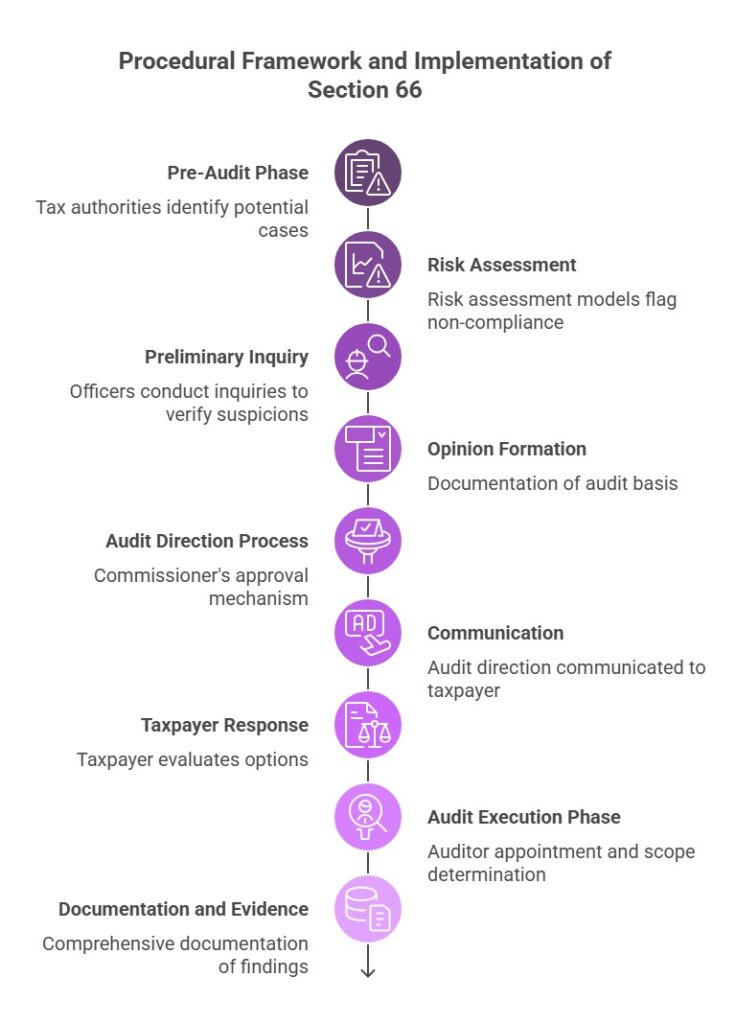

Procedural Framework and Implementation

Pre-Audit Phase

The implementation of Section 66 begins well before the formal audit direction is issued. Tax authorities typically identify potential cases through various means, including data analytics, routine scrutiny, or complaints from stakeholders.

Risk Assessment: Modern tax administration relies heavily on risk assessment models that flag cases exhibiting patterns associated with non-compliance. These models consider factors such as input-output ratios, filing patterns, payment behavior, and industry benchmarks.

Preliminary Inquiry: Before invoking Section 66, officers often conduct preliminary inquiries to verify their suspicions. This may involve calling for specific documents, conducting site visits, or analyzing available data in greater detail.

Opinion Formation: The statutory requirement for forming opinion based on prescribed circumstances necessitates careful documentation of the basis for proposed audit. Officers must clearly articulate how the taxpayer’s case fits within one or more of the three categories specified in Section 66.

Audit Direction Process

Approval Mechanism: The requirement for Commissioner’s approval introduces an administrative review of the proposed audit direction. This review should examine the adequacy of reasons, the appropriateness of proposed audit scope, and the selection of auditor.

Communication: The audit direction must be communicated to the taxpayer through proper channels, ensuring that they receive adequate notice and understand the requirements. The direction should specify the scope of audit, nominated auditor details, and completion timeline.

Taxpayer Response: Upon receiving the audit direction, taxpayers should evaluate their options, which may include compliance, seeking clarification, or challenging the direction through appropriate legal remedies.

Audit Execution Phase

Auditor Appointment: The nominated chartered accountant or cost accountant must accept the appointment and declare any potential conflicts of interest. Professional ethics require auditors to maintain independence and objectivity throughout the audit process.

Scope Determination: While the audit direction provides initial scope guidance, the actual audit scope may evolve based on findings during the examination. However, auditors must ensure that their examination remains within the broader framework established by the audit direction.

Documentation and Evidence: The audit process requires comprehensive documentation of findings, including identification of specific transactions or practices that support or contradict the authorities’ initial concerns.

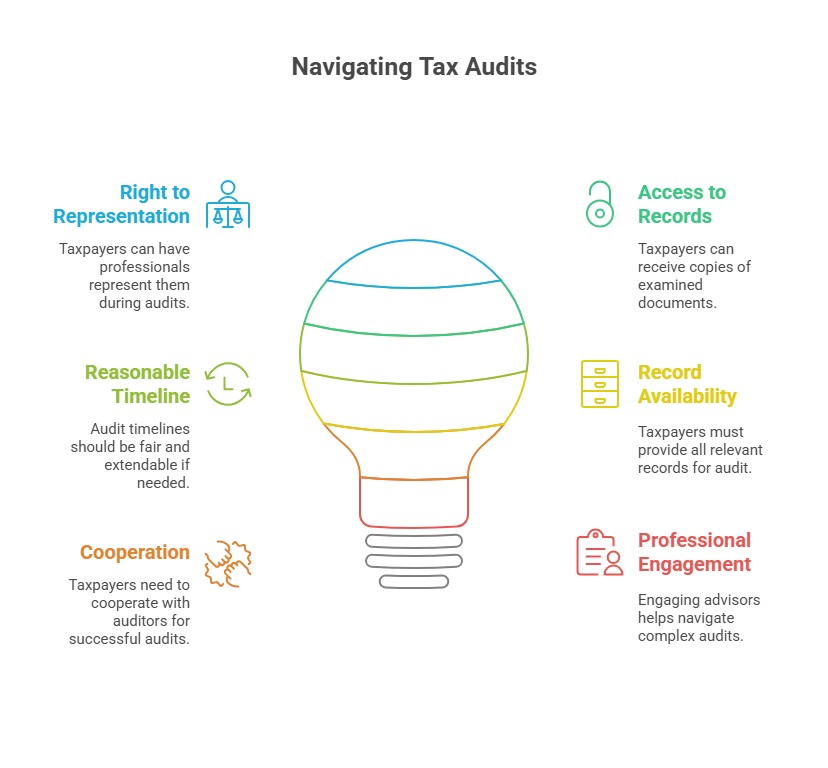

Rights and Obligations of Taxpayers

Taxpayer Rights

Understanding their rights becomes crucial for taxpayers subjected to Section 66 audits, as these rights provide important safeguards against potential misuse of audit powers.

Right to Representation: Taxpayers have the right to be represented by qualified professionals during the audit process. This representation can prove valuable in ensuring that the audit is conducted fairly and that taxpayer interests are adequately protected.

Access to Records: While taxpayers must provide access to their records, they also have the right to receive copies of documents examined by auditors and to understand the basis for any adverse findings.

Reasonable Timeline: The audit timeline specified in the direction should be reasonable, considering the scope of examination and the complexity of business operations. Taxpayers can seek extension if circumstances warrant additional time.

Compliance Obligations

Record Availability: Taxpayers must ensure that all relevant records are available for audit examination. This includes not only statutory books of account but also supporting documents that substantiate business transactions.

Cooperation: The success of Section 66 audits depends significantly on taxpayer cooperation. This includes providing prompt responses to auditor queries, facilitating access to premises and personnel, and offering explanations for apparently irregular transactions.

Professional Engagement: Given the technical nature of Section 66 audits, taxpayers often benefit from engaging professional advisors who can help navigate the audit process and ensure that their interests are adequately represented.

Impact on Business Operations

Operational Disruptions

Section 66 audits can significantly impact business operations, particularly for companies with complex transaction structures or those operating in multiple jurisdictions. The audit process often requires substantial management time and attention, potentially affecting normal business activities.

Resource Allocation: Businesses must allocate significant internal resources to support the audit process, including finance personnel, legal advisors, and senior management time. This resource allocation can affect other business priorities and may require careful planning to minimize disruption.

Documentation Requirements: The comprehensive nature of Section 66 audits often reveals gaps in documentation practices that businesses must address during the audit process. This may require reconstruction of transaction records or obtaining additional supporting evidence from third parties.

Long-term Compliance Implications

System Improvements: Many businesses use Section 66 audits as opportunities to strengthen their compliance systems and documentation practices. The detailed examination often reveals areas where processes can be improved to better support future compliance requirements.

Professional Relationships: The involvement of nominated professionals in the audit process can lead to ongoing professional relationships that benefit businesses in their compliance journey. These professionals often provide valuable insights into best practices and regulatory developments.

Recent Developments and Amendments

Legislative Updates

The GST framework continues to evolve, with regular amendments and clarifications affecting the implementation of audit provisions. Recent developments have focused on strengthening the audit framework while ensuring proportionality in enforcement actions.

Notification Updates: Various notifications have clarified procedural aspects of Section 66 implementation, including timelines, documentation requirements, and professional standards applicable to nominated auditors.

Judicial Interpretations: Courts have increasingly addressed issues related to Section 66 implementation, providing guidance on the appropriate use of audit powers and the rights of taxpayers during the audit process.

Technology Integration

Data Analytics: Tax authorities increasingly rely on sophisticated data analytics tools to identify cases suitable for Section 66 audits. These tools can process vast amounts of data to identify patterns that suggest non-compliance or unusual business practices.

Digital Documentation: The shift toward digital documentation has affected how Section 66 audits are conducted, with auditors now examining electronic records and using technology tools to analyze large volumes of data.

Best Practices for Taxpayers

Preventive Measures

Robust Documentation: Maintaining comprehensive documentation for all business transactions provides the best defense against adverse audit findings. This includes not only statutory requirements but also business justifications for apparently unusual transactions.

Regular Compliance Reviews: Conducting periodic internal compliance reviews can help identify potential issues before they attract authorities’ attention. These reviews should focus on areas commonly examined during Section 66 audits.

Professional Guidance: Regular consultation with tax professionals helps ensure that business practices align with regulatory requirements and that potential compliance issues are addressed proactively.

During Audit Process

Prompt Response: Responding promptly to auditor requests and providing complete information helps establish a cooperative relationship that can facilitate a smoother audit process.

Documentation Organization: Organizing relevant documents in a logical manner and providing clear explanations for business transactions can significantly reduce audit time and minimize disruptions.

Professional Representation: Engaging qualified professionals to represent taxpayer interests during the audit ensures that technical issues are properly addressed and that taxpayer rights are protected.

Challenges and Criticisms

Implementation Challenges

Auditor Availability: The requirement for nominations by Commissioners sometimes leads to delays when qualified professionals are not readily available or when conflicts of interest arise with potential nominees.

Standardization Issues: The lack of standardized audit procedures across different jurisdictions can lead to inconsistent outcomes for similar cases, creating uncertainty for taxpayers operating in multiple states.

Cost Considerations: While the Act doesn’t explicitly address audit costs, the practical burden of these costs on taxpayers, particularly smaller businesses, raises questions about proportionality and fairness.

Industry Perspectives

Compliance Burden: Industry associations have raised concerns about the compliance burden associated with Section 66 audits, particularly for businesses with complex operations or those operating in multiple jurisdictions.

Timing Issues: The timing of audit directions can sometimes coincide with critical business periods, creating operational challenges that may affect business performance.

Future Outlook

Evolving Audit Practices

The future of Section 66 implementation will likely see continued evolution in audit practices, driven by technological advances and changing business models. Authorities are expected to develop more sophisticated risk assessment tools that can better identify cases warranting special audit.

Artificial Intelligence: The integration of AI tools in tax administration may lead to more precise identification of audit cases and more efficient conduct of audits, potentially reducing the burden on both taxpayers and authorities.

Industry-Specific Approaches: Future developments may see the emergence of industry-specific audit protocols that better account for the unique characteristics of different business sectors.

Regulatory Developments

Harmonization Efforts: Ongoing efforts to harmonize GST implementation across states may lead to more standardized approaches to Section 66 audits, reducing compliance complexity for multi-state businesses.

Professional Standards: The development of specific professional standards for GST audits may enhance the quality and consistency of Section 66 audit reports.

Conclusion

GST audit under Section 66 represents a sophisticated approach to tax compliance verification that balances the need for thorough examination with taxpayer rights and procedural safeguards. The provision’s emphasis on professional expertise and specific triggering conditions demonstrates the GST system’s evolution toward more targeted and effective compliance measures.

The comparative analysis with Section 65 reveals how the GST framework provides multiple tools for different compliance scenarios, allowing authorities to choose the most appropriate mechanism based on specific circumstances. The case laws examined demonstrate judicial support for reasonable application of Section 66 powers while maintaining important safeguards against arbitrary enforcement.

For businesses operating in the GST regime, understanding Section 66 implications becomes crucial for effective compliance planning. The provision’s focus on record maintenance and value determination highlights the importance of robust documentation practices and transparent business operations.

As the GST system continues to mature, Section 66 will likely play an increasingly important role in maintaining compliance integrity. Taxpayers who proactively address potential compliance issues and maintain high standards of documentation will be best positioned to navigate Section 66 audits successfully.

The insights and guidance provided in this comprehensive analysis should serve as a valuable resource for tax professionals, business leaders, and compliance officers seeking to understand and effectively manage Section 66 audit implications. For further assistance with GST compliance and audit matters, consider consulting with the experts at TaxGroww, who specialize in providing professional guidance for complex GST situations.